News

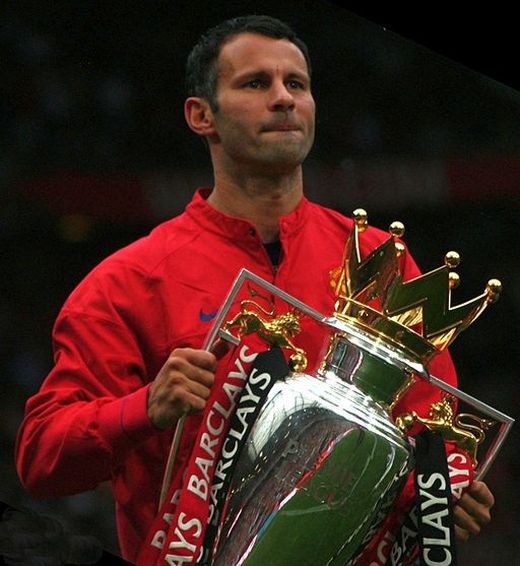

Ryan Giggs talks about achieving and maintaining excellence

Chris Brady, Professor of Management Studies at Salford Business School’s Centre for Sports Business, recently interviewed one of the university’s honorary graduates, Manchester United footballer Ryan Giggs, about achieving and maintaining excellence.

The interview was first published in the ‘Performance’ magazine which provides ideas and best practice for performance professionals in elite sport: www.leadersinperformance.com.

“Winning” is the central facet of high performance

On the same day Performance magazine sat down with Ryan Giggs, another interview – given by his former manager Sir Alex Ferguson – was published in the Harvard Business Review (HBR). Comparing the two interviews, what is striking is the similarity of the language the two men use regarding the central facets of high performance; not surprising given that they spent more than 20 years working together. In particular, one word dominated – “winning”.

When asked what types of characters he believes are essential to successful teams, Giggs answered immediately – “winners”. How did he explain this common but elusive concept? He says:

“Winners are people who will go to the edge to make sure that you win the game; and that includes in the week as well, in training. They would kick their teammates; they would do whatever it took. It would ruin their day if they lost a five-a-side game; it really means that much to them.”

Dependability and reliability

It is this “winning” characteristic that high performers seem to value above all others. But next on Ryan Giggs’ list was “dependability” and “reliability”:

“You need a group of seven or eight players who are going to be reliable week in and week out.”

Pushed to reveal what marks out the other three or four players Giggs was, perhaps surprisingly given his own reliability, not overly concerned. These players would include those who are considered to be game changers and who can, to a certain extent and for the benefit of the team, be accommodated.

The solid citizens in the team will put up with their relative unreliability for the benefit of the collective, Giggs thought.

In this respect he may be slightly at odds with Ferguson, who explained in his HBR interview:

“There are occasions when you have to ask yourself whether certain players are affecting the dressing room atmosphere, the performance of the team and your control of the players and staff. If they are, you have to cut the cord. There is absolutely no other way. It doesn’t matter if the person is the best player in the world. The long-term view of the club is more important than any individual, and the manager has to be the most important one in the club.”

Maintaining peak physical condition

Reliable or maverick, athletes must remain in peak physical condition to be able to perform on cue and the physical regime that has given Giggs’ career its longevity is now legendary, but how did it evolve? He says:

“I remember the moment. We were playing Bayern Munich at Bayern. I must have been about 28/29 and the day before the game we were training at Bayern’s stadium and I was playing the next day; the Gaffer had told me I was playing and he said, “swap teams” because one of their players was a bit of a dribbler so he wanted me to dribble against our guys. So, anyway, I got the ball and started to dribble and my hamstring just went.“At that moment, I was feeling really good, I was flying, I was beating players easily. I remember that I went back to the dressing room and I was gutted because I wanted to play – it was Bayern Munich versus United in the Champions League. I thought that I really needed to do something about this because I’d never had bad injuries, I’d never been out for more than six to seven weeks but my hamstring just kept recurring.“So I talked to the physios, I read up on anything I could find and from then on I changed my routine. I got a more comfortable car, not messing about changing cars every five minutes, changed my bed, changed my diet. I just tried to tick every box. I tried acupuncture, I used an osteopath which I still do to this day and I did yoga as well. I just tried to cover everything so that this wouldn’t happen again. You know, Champions League, injured, missing the game. I never did it to prolong my career; I just did it to play.”

Great players need to play, they need to be great

Ultimately, great players need to play, they need to be great and they need the stage upon which to demonstrate their greatness to the world. Ferguson puts it perfectly when he says:

“I expected more from the star players. I expected them to work even harder… That’s why they are star players – they are prepared to work harder. Superstars with egos are not the problem some people may think. They need to be winners, because that massages their egos, so they will do what it takes to win.”

What drives them on is the need to meet ever increasing challenges. Asked why he never played abroad, Giggs’ answer was simple:

“I’ve always wanted new challenges and I thought that every year at United there’s always been a new challenge. The time for me to go abroad was probably between 25 and 30 but I never got close to it, I just wanted to play for United. At that time I just felt the challenges at United couldn’t be beaten. I was 27 and we’d just won the treble so it never occurred to me. I’ve never thought that I missed a trick there.”

What are crucial elements of a successful team?

But what do great players believe are the crucial elements of a successful team? Which comes first, winning or team spirit? For Giggs it is the chemistry of the team under the guidance of a strong winning philosophy. United, he feels, had the winning mentality ingrained in them by Ferguson’s personal mentality and the traditions of the club for particular values such as trusting youth and taking risks to win. As Ferguson put in the HBR:

“I am a gambler – a risk taker – and you can see that in how we played in the late stages of matches… I always take great pride in seeing younger players develop. When you give young people a chance, you not only create a longer life span for the team, you also create loyalty. They will always remember that you were the manager who gave them their first opportunity.”

This has been the United way from the glory and tragedy of the Busby Babes through Tommy Docherty’s young team that brought United back to the top division in the 1973/74 season, to the more recent glories under Ferguson.

How to integrate new team members?

But how has this been achieved over such a lengthy period? How does the acculturation of incoming players work at United?

For Giggs it is about the way in which they are received and dealt with in the dressing room. He explains:

“New players are coming into a good dressing room, which makes transition easier. Also, training is probably more competitive than they’ve been used to.”

In his HBR interview, Ferguson asserts that a key to the maintenance of standards was

“never allowing a bad training session. What you see in training manifests itself on the game field. So every training session was about quality. We didn’t allow a lack of focus. It was about intensity, concentration, speed – a high level of performance. Each individual is welcomed according to their own personality.“A player can come in and have a compatible personality from the start. Ronaldo, for example, wasn’t at the standard he is today in the first couple of years but he was a likeable lad, he wanted to learn, he was a bit of a joker and he came into the dressing room quite easily. Others, who are quieter, they can earn the respect of their new teammates by what they’re doing on the training ground and in games. Robin [van Persie] instantly became a success because he was scoring winners every week. That made him difficult not to like.”

Both Giggs and Ferguson believe that building and maintaining mutual trust is a key element of high performance and as such has to be integral to the acculturation process. As Ferguson puts it:

“I would remind the players that it is trust in one another, not letting their mates down, that helps build the character of a team.”

Similarly, Giggs cites trust between the players as an important component of team performance.

Interestingly, previous research in this area seems to challenge this assertion. Taking NCAA basketball as his basis for trust and its relevance to performance within NCAA basketball teams, Kurt Dirks found that while trust is essential between the players and the coach and can even be an indicator of future performance, it does not appear to have any statistical significance between players.

Rewards would come as a result of consistent performances over time

However, are the same acculturation factors equally true of younger players, the lifeblood of United’s philosophy, as they come into the dressing room? Giggs has strong views on this.

He was reluctant to say “in my day” but in a sense it was inevitable.

“Sometimes, the problem with the occasional young player is that they expect, and get, rewards before they have really achieved anything. In my day I was told that rewards would come as a result of consistent performances over time. Don’t get me wrong, there are some great kids out there; I just don’t think there’s the hunger in young players in enough numbers as there was 20 years ago – I don’t just think that, I know it.“Because they’re getting the money early on and they’re getting cosseted, the hunger goes quite quickly. To be a United player they’ve got to be strong mentally to be able to put up with some of the stuff in the dressing room and on the pitch. You’ve got to be able to withstand getting kicked by Vidic, or Roy Keane or me and rising to it and being able to handle it. You’ve also got to welcome the pressure of the traditions of this massive club. Walking into the club and seeing the famous pictures – Charlton, Best, Law and Cantona – on the walls and saying to yourself: ‘That’s where I want to be in 15 years’ time’. That’s what it means to be a United player.”

Ferguson sums it up:

“The idea is that the younger players were developing and would meet the standards that the older ones had set.”He would have been proud of Giggs who has, from his earliest days at United, set the very highest standards for his successors to follow.

Ryan Giggs the coach

Giggs is now formally employed as a player/coach by Manchester United and will surely become a manager one day. Having completed his UEFA ‘B’ Coaching Licence in his early thirties and his ‘A’ Licence more recently, he is now part way through his UEFA Pro-Licence. He demonstrates his professional dedication to performing as a player by his ability to almost completely separate the two activities.

He tells an interesting story about coaching Antonio Valencia on a particular aspect of wing play and then deriving pleasure from seeing him performing the manoeuvre in a game. What was significant about his explanation was the casual aside that he had seen the event just after he had been involved as a player in the same game:

“I got subbed against Liverpool and was watching the game and saw Antonio do exactly what we’d worked on and I was really pleased.”

I asked Giggs if they’d discussed it after the game. “No,” he said. “We’d lost”. Giggs explains his ability to separate his two roles thus:

“The coaching is the hard part, the training and playing is what I’ve always done, and it’s almost a relief to get back to just playing. I don’t believe that I overthink the game; I think I’m playing just as a player. You’ve got your tools in your bag, you’ve been in the same situation thousands of times and you pull those tools out automatically.”

This ability to be able to pull out relevant tools as a consequence of hours of practice is now a common theme of modern performance theory, the ‘ten thousand hours’ made popular in Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers, and the power of practice. Giggs could be the perfect poster boy for the repetitive practice theory. As an example, he says:

“I wasn’t a good crosser, I didn’t need to be. I ran with the ball, I dribbled passed people. So, later in my career when maybe I needed other options I just had to get better at it and so I practised as often as I could. I practised from different positions on the pitch, on both flanks, ten yards into the opposition’s half, 20 yards, level with the penalty area, on the by-line (that’s where I was able to help Antonio). Practise, practise, practise.”

Penalties are mental, not technique

What about the age-old and surely now non-debate about penalties? Can they be practised? Of course they can – and should. Failure to score, according to Giggs, is predominantly about indecision:

“Penalties are mental, not technique. When I practised for the European Cup Final my mindset was that I’m going to put it in the same spot. If the keeper saves it, he saves it. I took 15 penalties and out of those 15 I scored 14 and hit the post with the other one. You’re not walking up to the spot thinking, should I put it left, should I put it right. Forget the keeper, it’s going where I practised. And don’t worry about missing in practice.”

Indecision can be caused, as Marc Sagal the US sports psychologist explains, by a failure to concentrate which in turn can often be caused by overthinking the consequences. This is surely the explanation for the world footballer of the year, Roberto Baggio, and his compatriot, Franco Baresi, voted the second greatest AC Milan player of all time, both missing the target by a good two feet in the 1994 World Cup final shoot-out against Brazil. Indeed, Giggs tells how his teammate Anderson demonstrated a complete indifference to the consequences when he too scored in the sudden death phase of the Champions League final against Chelsea:

“In Moscow, Anderson came on with two minutes to go in extra time. He’d never scored for United, he’s got that carefree character and he scored. That’s probably because he didn’t think too much about it; he just struck it down the middle.”

Whether it is supreme confidence in their own ability or a lack of concern about the consequences, the ability to be able to perform perfect technique under the greatest pressure is a mark of all great champions, like Giggs.